There is little contestation that realism is an enduring theory of international relations (IR). One strand of realism has its source in classical philosophy roots fixated on human nature. This is the assertion that human beings are the same everywhere, they strive to have an edge over others, they desire to call the shots to be in charge and not taken advantage of1. However, not all realists agree with this presupposition as explaining state behaviour in the system. This schism among realists will be a matter for consideration in detail later in this article.

Above all, the post-war period – the period after World War II (WWII)- marked the emergence of realism as a widely circulating perspective relied upon to contextualise and interpret international politics. Realism found currency and gained momentum among political science theorists and political elites in the United States, in particular. To a large extent, the US triumph in WWII helped shape and sharpen realist thinking among these scholars and the generality of realism proponents2.

Although there are several other IR theories at our disposal, we argue that realism remains the most useful starting point in understanding global politics. This should, by no means, suggest coercion into agreeing with its tenets. Rather, to favour realism is to sufficiently prepare the groundwork to critiquing it in part or in its entirety using those other alternative theories.

The international system itself can be viewed as a humongous virtual mass of moving parts and ideas. Multiple events are taking place at any given time, driven by a variety of actors. This thinking easily falls within the ballpark of liberal thinking. For the realist, however, while other actors may exist in the international system, the behavior of state actors, great powers in particular3, matter and is of any real consequence. For realists such as John Mearsheimer, although realism may not address all the questions, it has much to say about big questions in international politics4.

Anarchy in the System

Realism maintains that the state is in a constant state of flux. The most pressing concern of the state in the international system is its own survival. There is lingering possibility that a state or part of it may be taken over (Crimea-Ukraine) or completely fail (Somalia). For the realist, states exist in an international system that is engulfed in anarchy. Anarchy does not suggest lawlessness or breakdown of law and order, as would be suggested in a basic dictionary.

Rather, in realist terms, anarchy refers to an international system that lacks a higher political authority to which states submit or seek appeal. This is to say there is no higher power that could legitimately enforce rules and be obeyed in the international system. This is unlike the domestic system. In a domestic political system the state has overarching legitimate authority. It sets rules, and enforces rules and expects obedience to those rules.

If a neighbour trespassed into the backyard of another neighbour and began abusing property, they would probably be arrested within the hour. Not only that, but with possible restitution. The domestic system has such guarantees. There is a common saying among realists that the international system lacks a night watchman. This is akin to having no one to call to your rescue at 3am in the morning when your backyard is being invaded.

If no such guarantees exist in the international system, it is left to states to help themselves, as it were. This introduces the idea of self-help in the system, which we will take care to zoom in on later. Given the anarchy explained above, it becomes apparent why realists maintain that the fundamental goal of the state is its own survival.

Survival of the state in the system

According to realist reasoning, regardless of how good neighbourly relations may appear today, a state can never be certain of what is coming down the pipeline from its neighbours in 5, 10 or 20 years time. There is mistrust in the system5.

Realist logic rejects the utopian idea of perpetual peace in the world. For the realist, current peace is simply war in delay. Current cooperation and friendships merely postpone the inevitable break out of conflict to a later but certain date. That a generation or two have passed and no war has broken out between and among neighbours is no basis to rule out future conflict.

States ought to vigorously seek self-sufficiency as a matter of resolute national interest, according to realists. At its basic level, the idea of national strategic reserves of fuel and food, for example, as done by virtually all states in the world today, is in itself rooted in realism. This is a slick acknowledgment that there is no guarantee that your neighbour will want to continue trading with you or giving you access tomorrow as today. Today’s friend can be tomorrow’s enemy. It’s a matter of survival.

What states do to survive

Realism contends that states respond to the ever-lingering threat to their survival by accumulating as much power and doing so constantly. In essence, power is the ability to cause, influence or compel another state to do what they would not want to do. To the defense of realists, great powers in the world today do this all the time. They compel others to do what they would not want to do.

For the realist, there is no limit to power and there should be no limit to power. As times change and technology advances, what was power today may not be compelling power tomorrow. While power sources could be many including technology, economic and social in nature, the most potent source of power in international politics is military power. Socio-economic power is considered latent power, which is raw potential that could be translated into military power.6

Military power has been central to global politics since the birth of the idea of the state and remains the case today. It is set to remain the case for a very long time. Technological and economic advances essentially work to fortify military power. Unless you become militarily powerful, how do you secure, on a long-term basis, your economic success? Realists argue that the quest for more power creates a new problem in the international system. This problem is security dilemma7.

Security Dilemma explained

Security dilemma is an important part of realism theory of international relations. Due to the quest for more power, states inevitably find themselves in a precarious situation which itself sets them on a path to conflict and war. The following theoretical example is a simple illustration of how things play out in a security dilemma situation.

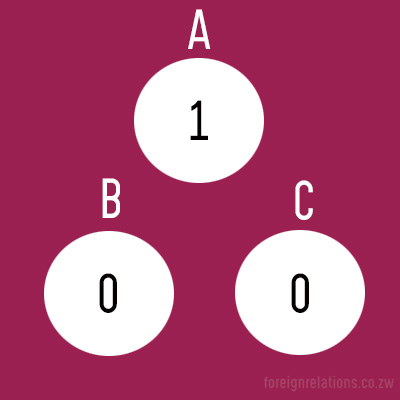

Stage 1

In the beginning State A has one unit of warhead. State A is, at this point, in domination or hegemony and could exercise power over State B and State C, which hold no matching military might.

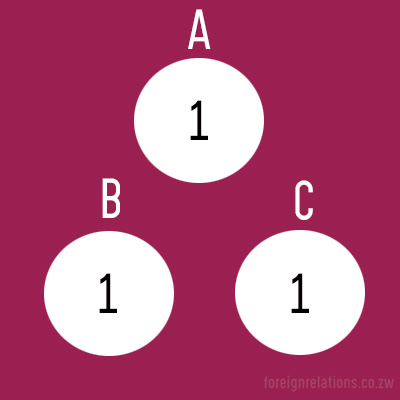

Stage 2

Because State B and State C recognize their apparent position of weakness viz State A, they also acquire one unit of warhead each to guarantee their survival

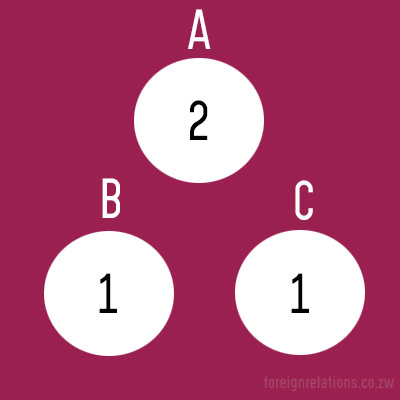

Stage 3

This leads State A, which is determined to remain powerful over State B and State C to enter into a new round of warhead acquisition. Due to the threat that both States B and C could have on State A if they came together, it is worth considering that State A may in fact want to acquire enough military power to destroy both States B and C in the event they jointly consider aggression against State A.

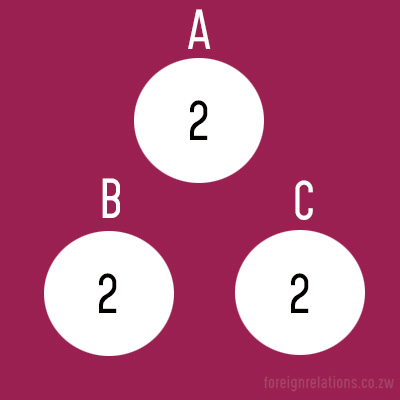

Stage 4

The action of State A to double its warhead stockpile in Stage 3 triggers States B and C into renewed pursuit for their own security. They proceed to acquire warheads such that among them they all have 2 warheads each. This causes State A to go a gear up in acquiring more weapons. The cycle continues. This indeed is the theory behind an arms race. Realists point out that this race is only broken by war and the cycle starts again. It is in this context that realists theorize that states in the system, are in fact in a state of permanent security dilemma8.

Strategy to delay war

In view of the imminent outbreak of war associated with the ever-escalating security dilemma as we have seen above, there has to be a strategic response. If state survival is a key tenet of realism, realist strategy in an environment of permanent security dilemma is to find ways to delay the start of the next war.

If war cannot be avoided, realist strategy dictates that at the very minimum, focus should be on reducing the scope and severity of the war. This would include locating theatre of war away from home in order to guarantee the continued survival of the state. The development of long-range missiles and complex missile defense systems can be viewed as an effective pursuit of this strategy.

Furthermore, in the modern world the United States provides the most useful example of such a strategy. Post WWII, the US is yet to fight a single war against any state on its own soil. This is despite having been involved in several of wars since the two world wars. The theatre of war has so far been located away from home although some may argue that 9/11 terrorist attacks challenge this proposition. This argument is down played by realist logic which pays little attention to non-state actors in the system

Self-help in an anarchic system

We earlier touched on self-help. This is a fundamental concept in realist thinking. For the realist, the idea of self-help is an inevitable feature of an international arena, which lacks an overarching authority to enforce order and administer justice. Self-help implies that states, as main actors in the international system, are left to devise own means to secure their survival. States take responsibility of their own continuity of which if ignored has existential implications.

Self-help mechanisms available to states would include threats, retaliation, negotiation and outright declaration of war9. We see these in use frequently around matters of territorial borders and trade, for example.

International law is a fallacy

Although much talked about and constantly pointed to, international law fails to make a mark among realists10. In the realist world, the purported ability of international law to keep states in check is sophism. In any case, the consequences of disobeying any international law are only felt after the fact often following a lengthy process. Consider the sometimes decade long due processes at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) or the International Criminal Court (ICC). To the realist, this dismally fails to guarantee national interest and state survival, which is a matter of now.

Furthermore, realists argue that international law is after all a creation of states themselves laden with self interest and therefore cannot be relied upon11. Even if international law were to be relied upon, it would remain handicapped lacking meaningful legs in the absence of a centralized means of enforcement in an anarchic system12.

It may be pointed out, however, that in the context of realism strategy, international law is often used and relied upon when it furthers certain realist objectives. Even so, there is always readiness on the part of the state to abandon this approach at a whim in defense of its survival. Law cannot cure the anarchic order of the international system. This makes self-help a necessity and therefore a permanent feature of the global political environment, at least for the realist.

State survival strategy in an anarchic system

Self-help dictates that states as rational actors in an anarchic system are least inclined to sit by and hope neighbours have no malign intentions against them. Self-help demands that states find means to survive and pursue key interests.

As stated earlier, realists assume that security dilemma brought about by anarchy inevitably leads to conflict. There are certain outcomes that follow the need to address security dilemma in the system. These outcomes delay the inevitable breakout of conflict although in the realist book they do not permanently prevent it. The following are state survival strategies in an anarchic system.

Balance of power and hegemony

Balance of power and hegemony are polarity strategies utilized by realists to delay war in an anarchic environment. Views differ among realists themselves pertaining to which of the two strategies to pursue. We mention here that balance of power and hegemony are realism strategies applicable at a regional level pertaining regional politics. It need not necessarily be exclusively at the international level.

Balance of power

Balance of power is a central feature of realism theory of international relations. Realists maintain that everything in international relations is built upon balance of power and that balance of power itself is critical to understanding international relations13. Balance of power potentially takes two forms namely bipolarity and multi-polarity. When two powerful states exist along side several other minor states in a neighborhood, for example, this represents bipolarity. This may also be the case at international level. It has been argued that a bi-polar international system emerged out of the rise of Russia out of the fallen Soviet Union to challenge the dominant United States. Yet others replace Russia with China.

On the other hand, multi-polarity exists in global politics when power is in equilibrium among a number of states such that no one state is more powerful than the other. This is more a reality in the contemporary world system at regional level. Certain regions appear to have “balanced-out” power.

Amassing enough power to become a dominant player in international politics is an expensive affair. This is often achieved by well-resourced and well-organized states and these tend to be great powers. It is for this reason that other states are inevitably relatively weaker. Weaker states play an important role in balancing power by aligning with certain powerful states or huddling together to form strong alliances. For the realist, these configurations are first and foremost measured in military terms; for it is military might that compels others to do what they would not want to do.

Hegemony

Hegemony in international affairs theoretically occurs both at regional and international levels. It is conceptualised in IR in terms of one powerful state asserting its dominance over other states by employing passive and coercive means14. In the current international system, it can be argued that hegemony is more common a feature of regional politics than global politics. Realist logic contends that the globe it too big with too much water, it is impossible to become a global hegemony15. Viewed through these lenses, the United States becomes a regional hegemony of the west.

As stated earlier, hegemony occurs when a single state enjoys dominance over other states in the international system. This results a unipolar system. There is general convergence in thinking among realists that the current international system is devoid of a single state with absolute hegemony. After taking into account China and Russia. What is left is a multipolar system.

Realist strategy is inclined towards maintaining regional hegemony while at the same time preventing other great powers from becoming hegemonies of their own regions. Examples include Russia’s dominance and influence in Eastern Europe, China in the South China Sea neighborhood both of which are not tolerated by the United States.

The logic here is that a great power that dominates its region becomes free to roam the world eventually getting into the back yard of the United States. If prevented from becoming hegemony in its own region, this keeps such a great power concentrating in its own region16.

A closer look at Realism camps

As stated in the introduction, realists are not all of the same camp. Two but important distinct strands of realism are human nature and structural realism. These two schools of thought proffer different approaches to explaining anarchy in the international system.

Classical Realism

Classical realism is on many occasions also referred to as human nature realism. This is consistent with its roots embedded in human nature as put forward by classical philosophers notably Thucydides (c. 460–c. 400 B.C.E.), Machiavelli (1469–1527) and Hobbes (1588–1683).

According to classical realism logic, the egoistic nature of human beings holds international politics captive. There is little room for morality. Self-interest that’s inherent in human beings overpowers any sense of morality. Put simply, self-interest is prioritized over morality. For classical realists, power is an end in itself. According to Hobbes, individuals are wired to ‘a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceases only in death’17.

To the classical theorist, questions to do with right or wrong cannot halt the pursuit of opportunities to increase power and strength. Classical realists would point to the behavior of states in the international system regardless of which individuals are in charge of the state. A change in human leaders at state level seldom results in any change in state behavior in the system. The reason lies in the inherent human nature, according to classical realists.

For Machiavelli, moral and immoral means are equally justified to further self-interest. In other words ‘the state has no higher duty than of maintaining itself’. Although classical realism has roots in traditional political philosophy, well known modern classical realists include E. H. Carr (1892 – 1982) and Hans Morgenthau (1904 – 1980).

Structural Realism

Often referred to as structural theory or neorealism, structural realism is most concerned about the anarchic nature of the international system. Unlike classical realists who point to human nature, structural realists point to the architecture of the international system itself to explain state behavior in international politics. It need not matter which state it is. All states conform to certain behavior due to the make-up of the system.

That the absence of a higher authority in the international system causes states to default to self-help is an important tenant of structural theory. Hobbes’ conceptualization of the individual and society, were there is war ‘of every man against every man’ 18 forms the foundations of neorealism.

According to Hobbes, in the state of nature, each individual is his or her own keeper. There is no government (anarchy) and everyone enjoys an equal status. In order to survive, one must be ready to respond to force using force. For structural realists, power is a means to an end. The ultimate end is thus survival. Invasion is a feature of Hobbs’ state of nature occasioned by limited resources. Invasion is a possibility without warning. There is an ‘endeavor to destroy or subdue one another’ 19 in order to gain safety and security. Peace cannot be guaranteed.

Although Hobbesian thought concerns the individual and society, structural theory logic elevates Hobbs ideas to explain the architecture of the international system involving states. Structural realists argue that in a similar fashion that the individual is not secure in the state of nature, so are states in a system lacking an over hanging authority. The idea of anarchy that dominates neorealist thought is central to Hobbesian thinking.

Structural Realism Assumptions

John J. Mearsheimer, one of the leading lights among structural realists, identifies five assumptions undergirding structural realism20. Many of these have already dominated our discussion as here summarized.

- Anarchy, there is no higher sovereign authority in the system

- All states possess some offensive military capability to cause some degree of harm

- There is a lack of certainty about the intentions of another state good or bad. Even if you could know a state’s intentions today, you may never be certain of its future intentions.

- The principle (but not only) goal of a state is survival. Unless you survive, you can’t pursue any other goals e.g. human rights, prosperity and so on.

- States are rational actors, they are strategic calculators. They calculate what they need to do to survive.

According to Mearsheimer, when these assumptions are put together they produce three forms of state behavior;

- Fear – states fear that they may end up living next door to a state with malign intentions. There would be no one to call for help, on account of anarchy

- Self-help – states resort to taking care of themselves in view of number 1 above

- Power maximization – states seek to be very powerful as a way of securing themselves.

Offensive and Defensive Realism devide

Within neorealism itself, further stripes exist allocating structural realists into two main camps. If power maximization becomes the behavior of the state, these differences emerge between structural realists in answer to a fundamental question concerning how much power is too much power.

Defensive Realism

Defensive realists remind that the structure of the international system in of itself encourages states to go to war. For defensive realists, there should be conscious restraint to gaining more power. An attempt to pursue hegemony or to increase power relative to other great powers in the system is a recipe for trouble.

Defensive realists contend that a great power that amasses more power changes the balance of power, which in turn gets other great powers in the system very nervous. Due to the nature of the system, this triggers containment, which may result in the growing power to be crushed.

It is through the lenses of this logic that defensive realists consider realism a theory of peace at heart. Their strategy is for a great power to concentrate on maintaining the balance of power instead of deliberately causing imbalance in the system. Were balance of power is maintained, peace is present. Notable defensive realists include Kenneth Waltz.

Offensive Realism

Kenneth Waltz is opposed in this view by John Mearsheamer a sworn offensive realist who stands on the other side of the divide. Offensive realists argue that it is strategic for states to pursue more power and were conditions are right, hegemonic ambition.

The logic here is that overwhelming power relative to others is the only way to secure survival in an anarchic system. This, at heart, is a thorough Hobbesian worldview. The ultimate goal is to be hegemony and this may mean going to war in some cases.

Conclusion

Realism is an enduring IR theory, a tool to be used to explain global politics and to account for the behavior of states in the international system. It has roots going back to early philosophers such as Thucydides, Machiavelli and Hobbes. This points to a long tradition. The end of WWII encouraged the development of neorealism, which has since been the dominant theory of international relations among many scholars, academics and policy makers. Key elements that define realism include anarchy, self-help, balance of power and distrust among states in the system. These factors drive states to seek power in order to be secure for the sake of survival. Although structural realism is now the dominant strand of realist logic, within it are stripes in the form of defensive realism and offensive realism. Defensive realists discourage states from amassing more power as a security strategy while offensive realists believe that it is prudent for states to acquire as much power as possible to become secure. Realists acknowledge that realism, as a theory, does not answer all questions. However, they argue that their theory is key to explaining big questions in international politics and that it is these big questions that really matter.

Are you a realist? Take the Realism Test

If you believe that states are prone to go to war against each other, you are probably wired to think like a realist.

References

- R. H. Jackson, G. Sørensen, Introduction to International Relations: Theories and Approaches, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2007.

- S. Guzzini, Realism in International Relations and International Political Economy: The continuing story of a death foretold, London and New York, Routledge, 1997.

- R. H. Jackson, G. Sørensen, Introduction to International Relations: Theories and Approaches, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Structural Realism – International Relations: Part 1, [online video], 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RXllDh6rD18, (accessed 12 June 2019).

- Theory In Action: Realism, [online video], 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UnKEFSVAiNQ, (accessed 12 June 2019).

- T. Dunne, M. Kurki and S. Smith, International Relations Theories: Discipline and Diversity, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Realism, [online video], 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eoqvax-b6JM&t=218s, (accessed 12 June 2019).

- ibid.

- J. Donnelly, Realism and International Relations, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- ibid.

- ibid.

- M. Noortmann, Enforcing International Law: From Self-help to Self-contained Regimes, London and New York, Routledge, 2016.

- R. Little, The Balance of Power in International Relations: Metaphors, Myths and Models, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- O. Worth, Rethinking Hegemony, London, Palgrave, 2015.

- Offensive Realism in Explaining the Current and Future US-China Relations, [online video], 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ReSWxNGtzjE, (accessed 13 June 2019)

- ibid.

- T. Hobbes, The Leviathan,[website], 1660, https://www.ttu.ee/public/m/mart-murdvee/EconPsy/6/Hobbes_Thomas_1660_The_Leviathan.pdf, (accessed 14 June 2019)

- ibid.

- ibid.

- Offensive Realism in Explaining the Current and Future US-China Relations, [online video], 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ReSWxNGtzjE, (accessed 13 June 2019)